On Sept. 1, the Taylor City Attorney’s Office received its first batch of requests from property owners on the town’s outskirts to remove themselves from the grips of municipal development rules.

It was the first day for a new law passed by the 88th Legislature in May, with lawyers for developers and sellers locked and loaded to start the process known as de-annexation.

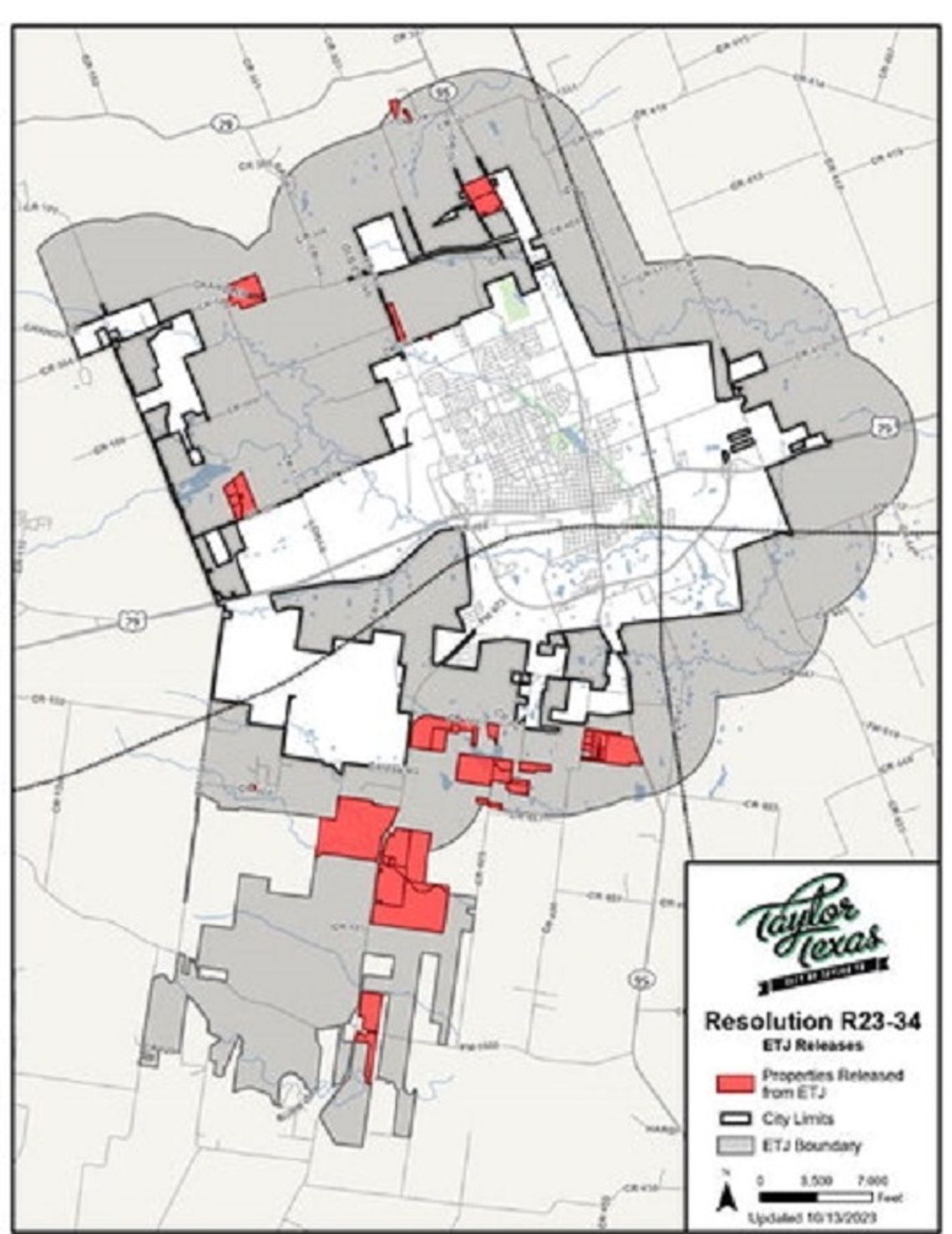

The result is that dozens of properties in Taylor’s extraterritorial jurisdiction, also known as the ETJ, have been removed from the buffer zone around the city and are no longer subject to development oversight or future annexation.

The first batch of properties were officially removed from Taylor’s ETJ on Oct. 12 at a City Council meeting.

Approval for another batch of applications was slated for an Oct. 26 council meeting.

The city’s hands are tied thanks to the new law. The process puts the tracts back into unincorporated areas, where development codes and land regulations are far less stringent.

In all, there are 30 to 35 properties totaling 2,184 acres uncoupling from the Taylor ETJ, according to a city official.

Those tracts of land include several abutting or near the vast acreage owned by Samsung Austin Semiconductor, a local subsidiary of South Korean-based Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd.

“We all are looking at when the dust settles, what’s this all going to look like?” said Tom Yantis, Taylor assistant city manager. “This is just the first wave.”

The effort to provide an easy path to leave an ETJ came about because of developer and landowner discontent with Houston and surrounding cities wielding power outside the city limits.

In addition to having approval for development in the ETJ, cities could collect sales taxes generated by businesses on the properties but were not required to extend public services to businesses or residents in the outlying areas. Also, residents couldn’t vote in city elections.

By the time the law passed the state Senate on a 20 to 10 vote, developers were already getting their ducks in a row to pull land from ETJs around the state, including an avalanche of filings for Williamson County properties.

For some landowners, de-annexation is a way to increase the value of their land in a future sale to a developer. Some of the would-be sellers on the outskirts of Williamson County cities are elderly or have inherited land and are ready to cash in.

For them it’s a win. The victory for developers is that cities cannot dictate what can be built on the land or how it should be built, which in some cases are deal killers because it limits the possible profits that can be made from a project.

Austin-based regulatory law firm Cobb & Johns used Taylor’s ETJ, without naming it, as an example for why landowners wanting to sell should petition for de-annexation.

“You may see your property value increase — by a lot. For example, ETJ residents in a small Central Texas city were dealing with a municipality that had killed over $100 million in land deals, with the city telling ETJ residents living close to a new $25 billion plant that they could not develop their land for anything other than agriculture or rural-residential purposes,” Cobb & Johns lawyers wrote on the firm’s website.

“Once able to remove their land from the ETJ, some of these residents saw their land values increase from a range of $30,000 to $50,000 per acre to a range of $110,000 to $315,000 per acre. That’s an increase of two to six times for some of these folks,” the law firm wrote.

Cobb & Johns, which represents several property owners in Williamson County ETJs, also said it was highly likely that cities would eventually find a way to reassert authority over parcels of land outside the city limits.

While petitions are coming in heavily now to take advantage of the new law, it would likely take lobbying the Legislature in a future session for a bill to give cities that authority or a workaround.

Litigation also is a possible — but costly — path to regaining control of a contiguous ETJ.

The contiguous nature of ETJs since they were created 70 years ago are the main reason cities opposed de-annexation. Gaps from one part of the territory to another can create havoc for city and utility planners.

“The legislation creates pockets in the ETJ and infrastructure is based on straight lines, like those for water lines, sewer lines and roads,” Yantis said. “We don’t know how many and when properties are going to leave the ETJ. It really makes it hard for the city plan for the future of the city’s infrastructure.”

It only takes a petition or vote representing 50% of the population in an area or tract of land to be officially removed from an ETJ.

In the case of most of properties in Williamson County, each petition represents just one petitioner or voter so there isn’t a need for a formal election or campaign of pros and cons.

Most of the petitions to date have been for land in the southeast portion of the ETJ, including large and small plots just east of Samsung’s land and stretching south of the chipmaking facility’s border to almost the southern tip of the ETJ.

A few scattered properties now out of the ETJ are west and north of the city.

This is the second blow in recent years for cities trying to control growth around them and also capture property-tax dollars from development. Earlier legislation made it impossible for a city to annex land or neighborhoods without a vote of residents, something not required for decades.

Large companies, especially those in manufacturing, prefer some sort of buffer to residential development around their land because the two don’t always make good neighbors.

Yantis said Samsung officials have expressed concern about residential growth close to their boundary, “but we won’t have land-use controls if the properties can’t be annexed.”

Samsung has not issued a formal statement on the situation.

For now, the city is trying to control what it can to provide services north of U.S. Highway 79 and near the Taylor municipal airport so new development can happen smoothly.

Development in the areas removed from the ETJs will now be subject to county regulations, which will create additional work for Williamson County development staff, Yantis said.

The city has ongoing conversations with the county to try and keep the standards close so the restrictions or lack of them, so developments aren’t wildly different from one side of a road to another.

“And we try to speak with one voice on the county transportation plan,” he said.

While workarounds, right-of-way acquisitions and other maneuvering may be necessary to deal with the gaps in the ETJ, it is unclear just how much de-annexation will ultimately complicate the future.

“We’re going to just focus on what we can do now,” Yantis said.

AT A GLANCE

- State law now gives property owners in a city’s ETJ the power to de-annex.

- De-annexed properties on city’s outskirts subject to less regulation and control, cannot be annexed again.

- Taylor has already seen 30 to 35 properties de-annexed for 2,184 acres.

- Lawmakers approved the measure after hearing complaints from the Houston area.

- Some predict lobbying by cities eventually could restore control.

Comment

Comments