In just a few short months, Samsung Austin Semiconductor’s Taylor fabrication facility will open for business producing microchip technology to reduce U.S. reliance on foreign markets.

And, although full operations are delayed until 2025 according to parent company Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. in South Korea, the plant will begin to reduce its dependency on Taylor for all its water needs and turn to the Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer for the rest.

That plan concerns some, including members of communities already depending on the aquifer for water, work and agriculture.

Complicating matters is the fact San Antonio, the seventh-largest city in the nation, is also tapping into the aquifer.

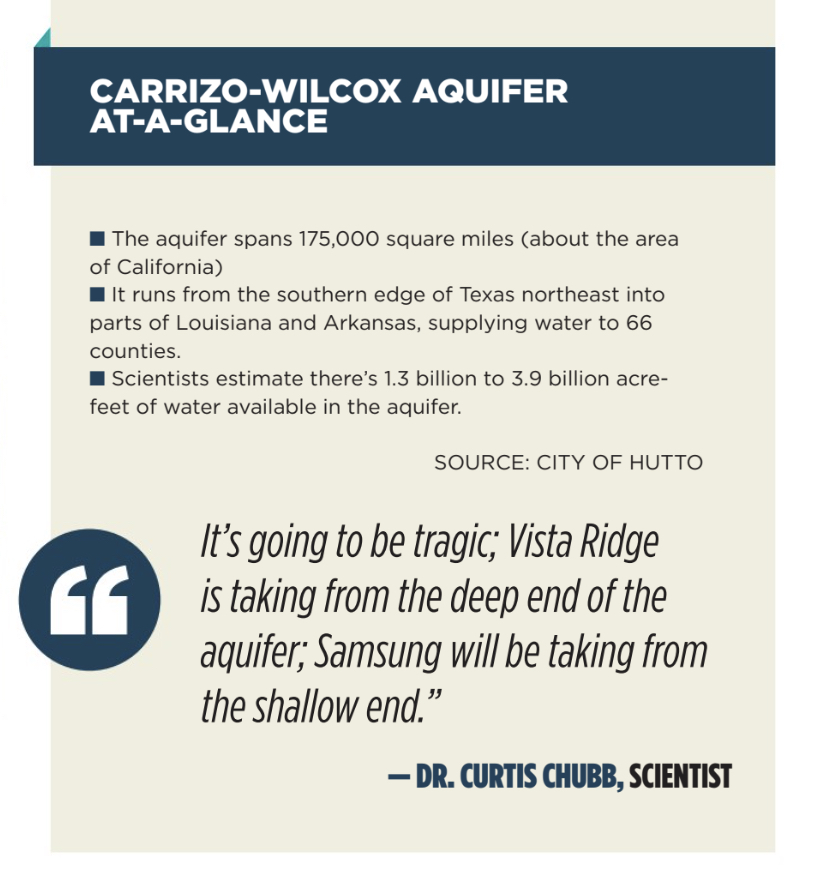

Cattle rancher and Milam County resident Dr. Curtis Chubb, a former medical researcher, has long warned about over pumping the aquifer.

Chubb, a member of the Central Texas Aquifer Coalition, would like to see a more pragmatic approach to water conservation in the aquifer before it’s too late.

“Who says stop the pumping? No one. It’s all self-policing,” Chubb said.

According to hydrological research, from 2020 to 2023 the Carrizo-Wilcox is down 168 feet. So are neighboring aquifers.

.png)

THIRSTY SAMSUNG

During the first quarter of 2024, according to an interim water schedule, Taylor will supply Samsung with 4.63 million gallons a day of potable water.

After that, the amount decreases to just under 1 million gallons of water a day through the life of the agreement.

How much Samsung will draw from the Carrizo-Wilcox has not been made public, but what is known is the plant needs 15 million gallons of water a day for operations alone.

Considering most people use only 70 to 100 gallons of water a day, it’s no small drop in the bucket, but the Carrizo-Wilcox is huge.

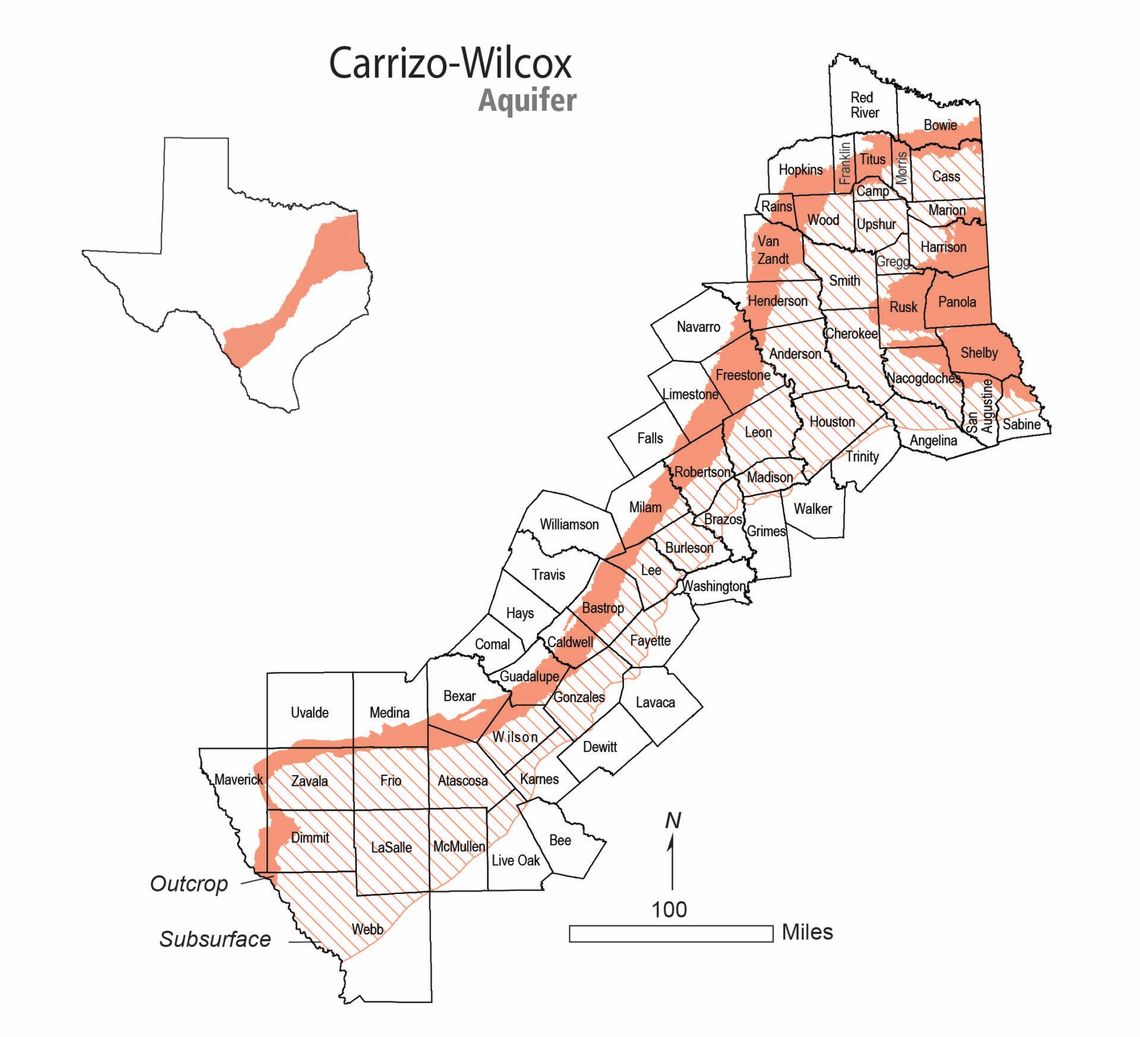

The aquifer spans 175,000 square miles (about the area of California) and runs from the southern edge of Texas northeast into parts of Louisiana and Arkansas, supplying water to 66 counties.

Scientists estimate there’s anywhere from 1.3 billion to 3.9 billion acre-feet of water available in the aquifer.

An acre-foot is the amount of water needed to cover 1 acre of land with water 1 foot deep, almost 326,000 gallons.

Fewer than 10 years ago, the Carrizo was considered primarily untapped with trillions of gallons of water there for the taking.

Water marketers swooped in, bundled water rights and sold them to corporations and municipalities.

Georgetown being one of them. In August 2023, the city entered a reservation agreement with a water marketer for 35.2 million to 62.5 million gallons of water per day from the Carrizo.

VISTA RIDGE

Another project, Vista Ridge, is pumping 56,000 acre-feet or 16 billion gallons of water a year to a thirsty San Antonio as part of a San Antonio Water System initiative.

Officials said the 142-mile pipeline is providing water to more than 194,000 homes, accounting for 14% of the city’s water needs.

According to the Ground Water Assistance Program, since Vista Ridge started pumping in 2020, over 125 wells in Milam, Burleson and Lee counties have either started sucking air or dried up.

The GWAP was established to assist property owners who experience problems with their wells due to large-scale pumping and is fully funded by the corporations producing or exporting water from the Carrizo.

Since 2020, GWAP has paid out over $2.1 million to fix property owners’ wells.

But that’s the easy fix; state records show the average annual recharge rate of the Carrizo is 25,500-acre feet per year.

Which means Vista Ridge is drawing down the aquifer before Georgetown or Samsung even start pumping.

Chubb said the rate at which the aquifer is being pumped is unsustainable.

As a preview of possible things to come, Chubb points to a study he conducted in 2019 on the Alcoa mining operation at Sandow and Three Oaks.

From 1988 to 2010, the company pumped an average of 23,000 acre-feet a year out of the aquifer in roughly the same area that Samsung will be drawing from.

His research shows water levels dropped so low that Alcoa had to either modify or replace 485 landowner wells in Milam and Lee counties between 1988 and 2009 and over 20 years later water levels still haven’t recovered.

Chubb says several hydrological studies show an extremely low recharge rate in that area of the aquifer of less than 4,000acre feet a year, with less than 10% of the total recharge entering the deeper portions of the aquifer.

Alcoa reported that it “anticipated that complete recovery of the aquifer would take approximately 100 years” after the pumping stopped.

Chubb says Vista Ridge alone takes over five times more water than Alcoa did, so the recharge from that project could take 500 years.

The man in charge of the health of the aquifer in that area, Gary Westbrook — general manager of Post Oak Savannah Groundwater Conservation District — acknowledges problems accompany large-scale water projects.

“We are going to have impact, there’s no way around it. The question is, how do you deal with it?” Westbrook said.

During a presentation to the Legislature in 2022, Westbrook talked about what his district is doing to protect the aquifer and the people who rely on it.

With 420 monitoring wells and a litany of predictive model testing, they do all they can to prevent what is neither convenient nor cheap.

Landowners whose wells are affected must lower their pumps or dig deeper to find water.

Westbrook said there’s only one way to prevent future issues, and it comes down to the almighty dollar.

“In order to secure large-scale pumping rights, you need acreage, so someone is getting paid. If we can get our landowner to not sign up to participate in large water projects, then we will curtail large-scale projects in the future,” he said.

Chubb sees things differently, “I blame the groundwater district who gave out the permits.” Chubb said.

He noted Post Oak has issued 40-year pumping permits instead of the standard five and wants board members replaced because of it.

IN DECLINE

According to Nature research data, 82% of Texas’s aquifers are in some form of decline.

While most of the drop is protracted rather than punctuated, in over a quarter of Texas’ underground basins, 28% are receding at twice the rate in the 21st century as they did in the end of the 20th.

According to the 2022 State Water Plan from the Texas Water Development Board, hydrological demands are projected to increase by 9% over the next 50 years, while existing water supplies are projected to decline by 18% during the same time. That means the water supply in Texas will not meet the demand by 2070, critics said.

In response, the 88th Legislature in 2023 passed Senate Bill 28 and Senate Joint Resolution 75 providing for the creation of the Texas Water Fund.

In addition, SB 30 authorized a one-time, $1 billion supplemental appropriation of general revenue to the fund.

The money will go toward securing alternative water sources for Texas, including marine desalinization and oilfield water reuse.

Texas desalinated ground and surface water represent an increasing component of the state’s water supply.

In 2020, TWDB reported that Texas has more than 2.7 billion acre-feet (880 trillion gallons) of brackish groundwater available in 26 of its major and minor aquifers.

Comment

Comments