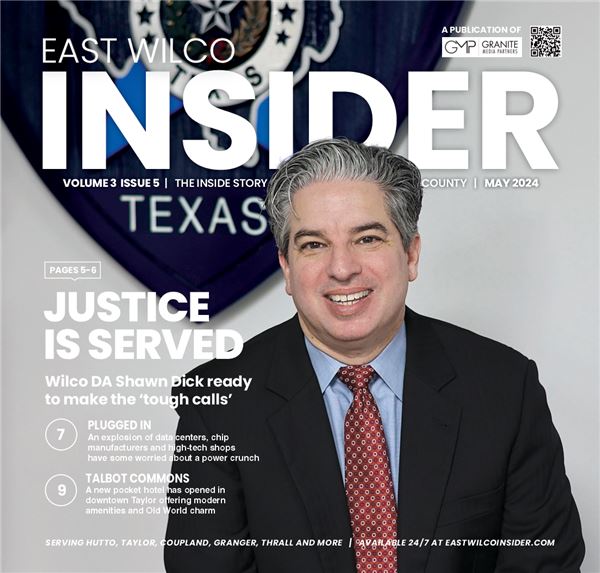

CARING

SWAMPED WITH STRAYS Crowded shelters exceed capacity

Williamson County shelters are struggling to cope with growing numbers of homeless animals.

The population of strays and surrenders — pets brought to shelters by owners who can’t or don’t want to keep them – is growing almost as fast as the county’s human population.

The Williamson County Regional Animal Shelter is by far the largest operation in the area. It serves Hutto, Leander, Round Rock, Cedar Park and other towns without their own animal shelters.

“We have been on what we call critical capacity since May of last year,” said the shelter’s Community Programs Coordinator April Peiffer.

In 2019, WCRAS, located at 1855 S.E. Inner Loop in Georgetown, added more than 60 new dog kennels, 93 cat kennels and a new adoption building – a $10.5 million project.

“The shelter was designed to accommodate a maximum of 110 dogs comfortably, and we are staffed to care for 110 dogs. We’ve had well over 170 dogs for some time now,” Peiffer said. “We are stretching our resources as far as they can go.”

She added, “Now kitten season has started, and we’re going to be overrun with kittens very soon.”

Guinea pigs, rabbits and other small animals are brought in, too.

“A lot of people are having trouble affording their pets. It’s the economy,” Peiffer said. “Everything has gone up… vet care, food, toys, medicine, supplements — all cost more. On top of that, some apartment complexes have rules that are very arbitrary, and they may have large pet deposits.”

WCRAS Director Misty Valenta said one of the organization’s primary goals is changing community concepts of what a shelter does.

“For the longest time animal shelters preached to people to ‘bring ‘em in.’ That’s what the community has grown up with,” she said.

That is no longer a possibility. WCRAS, like most shelters in the fast-growing Austin area, takes very few surrendered pets. Instead, they are “family-friendly.” In shelter terms, that means helping families find ways to keep their pets or to find them new homes. A volunteer support group, Fans of WCRAS, helps raise funds, donates supplies and more.

“The number of services we are asked for has grown significantly,” Valenta said. “Roughly, we get about 7,000 animals every year.”

Last year, she said, more than 65% of the animals brought in were adopted. Others were lost pets reunited with their families, and about 10% were transferred to some of the animal-rescue societies in the area, such as Blue Dog Rescue or Shadow Cats.

The feral cats brought in from the shelter’s trap, neuter and release, or TNR, program were returned to their feral colonies. The shelter has been “no-kill” – defined as euthanizing 10% or fewer animals – since 2010. Last year the euthanasia rate was 2%.

Meanwhile, city leaders in Taylor considered merging their animal shelter with the larger Wilco space awhile back. It never happened.

“A few years ago, they were talking about whether to keep the shelter or partner with Williamson County,” said Taylor Animal Shelter Director Sandy Perio. “But they didn’t do it because of public outcry. Citizens told the (City) Council they wanted to keep their shelter.”

Perio added, “During the COVID shutdown, we were one of the only ones that didn’t at least partly close down, and we took in more animals than we ever had. We were even taking owner surrenders. But most weren’t here for more than a day or two. All the rescue groups were pulling from us. But when things opened up and the housing market started rising, suddenly we are just drowning with so many animals. Austin shelters and Williamson County are just overflowing.“ Some relief is imminent. Construction has begun on a project that will add 13 dog kennels to the present 17. A new building with 18 cat condos and a big adoption room will replace the nine cat cages in a ragged cinderblock building that served as the original shelter back in the 1950s.

It’s a huge improvement, but Perio notes the shelter is still understaffed.

“Before they started on construction, I told the city manager that I won’t take in more animals than we can take care of properly. I think it’s inhumane to make dogs live in popup carrier cages.”

She added, “It’s sad that we get a lot of animals dumped in Taylor, mainly because surrounding shelters are full and won’t take any more animals or they are not completely no-kill. Milam County borders us, and there’s basically nothing available there. When somebody wants to give up a pet but wants them in a completely no-kill shelter, they dump them in our parks.”

The lack of nearby, affordable medical care for pets is another concern, Perio said.

To alleviate the problem, Perio made an agreement with Humane Educators of Texas, a school for vet techs and animal control officers in Hutto. Austin-based SAFE Refuge, or Saving Animals from Euthanasia, helped buy surgery equipment that is kept at the school, and they microchip and administer medicine.

“The Taylor Police Department has been very supportive from Day One,” Perio added. She also praised developers of a new subdivision, Avery Glen.

“On their homeowners’ Facebook page they did an album of pet pictures,” she said. “People who live there posted photos of their animals, so if they get out and somebody finds it they can scroll through and see if it belongs to one of their neighbors.”

The shelter’s nonprofit “friends” organization, Texas Critter Crusaders, plays a critical role, Perio added.

“They volunteer and put on free spay and neuter events. They raise funds for us and advocate for us at City Council,” she said. “They have a feral TNR program, and they pay for any meds we need and microchips, and more. The best thing way you can help us is to donate or get involved with them,” she said.

Texas Critter Crusaders co-founder Melanie Rathke has been volunteering at the Taylor shelter since 2015 and started the nonprofit the next year.

“Our primary goal was to keep animals out of the shelter, which includes helping with spay and neuter, and helping people whose pet has an illness or injury they can’t afford to fix,” Rathke said. “We have gone to council many times to get them to realize their budget did not meet the city’s needs. When we started, the shelter’s medical budget was $3,0900. Now it is more like $25,000.”

Critter Crusaders still raises funds and offers consistent volunteer services. In February, the group put on a free spay and neuter clinic with Animal Balance, another low-cost vet organization. In three days (one set aside for feral cats), volunteers spayed and neutered 199 animals.

Rathke trapped many of the cats, held them overnight, and ferried them back and forth to be “fixed” at the event, then released them to their feral communities. She and the other volunteers were trained by Shadow Cats.

Rathke said she found an unexpected animal advocate in Thrall’s mayor, Troy Marx.

“We helped him get a TNR program started for feral cats, and we’re going to do a free microchipping event in Thrall … Believe it or not, Thrall has a holding area for strays at their Water Department,” she said. “Their police chief is a huge animal lover. They will try to adopt dogs before they take them to the Wilco shelter.”

There also is a new veterinary clinic in Granger. “We did free microchipping for the vet there — 151 animals so far this year,” Rathke said. “I wish every town had their own shelter. … We need to take care of our own.”

The number of homeless animals keeps increasing. While the WCRAS budget increased last year from $2.6 million to $2.8 million, it may need another significant jump if Georgetown’s city leaders decide to turn the city’s local operations over to the regional shelter, as Hutto and other towns have done.

The Georgetown City Council is currently studying the prospect.

Advocates say it could save the city up to $300,000 a year, even with a $500,000 contribution to WCRAS for taking on the added responsibility — and animals.

“Georgetown has had its own shelter for quite a while. I started here as a volunteer in 1988,” said Georgetown Animal Shelter marketing coordinator Shawn Gunnin.

“We’ve been full for most of the last year. Since spay and neuter clinics were just about nonexistent during COVID, there was exponential growth. Now, a lot of people can’t afford it. … We refer people to low-cost places like Emancipet, but you have to book months in advance.”

She added, “We’re so small compared to the county shelter. We have a good staff and a good core group of volunteers, and we’re maintaining at the moment.”

Top: Texas Critter Crusaders is a local nonprofit working to aid the Taylor Animal Shelter, with assistance from Sareena Howell (left) who fosters animals with medical problems, and Crusaders President Melanie Rathke. Below: Grace Terry at the Williamson County Regional Animal Shelter in Georgetown visits with a friend. Courtesy photos

Comment

Comments