FERNANDOCASTRO

With the blistering days of summer here and folks watching their pennies, families can still have a fun but educational activity while staying close to home.

Why not pay a quick visit to a few of the dozens of historical markers in eastern Williamson County detailing high — and maybe low — points in the saga of the Lone Star State?

Not only will you save gas, you might learn something.

It’s not hard to find a link to the past in these parts, including perusing the many historical markers at churches and cemeteries such as The First Baptist Church of Taylor, 300 N. Robinson St.

Based on a completely unscientific survey, here are five of the most interesting historical spots in our own backyard.

DR. JAMES LEE DICKEY 500 Burkett St., Taylor

Texas Historical Foundation board member Judy Davis (front row, second from right) joins Williamson County and Taylor city leaders during a ceremonial check presentation for the Dickey Museum and Multipurpose Center, site of the Dr. James Lee Dickey historical marker. A suspicious fire last year heavily damaged the site. PHOTO BY FERNANDO CASTRO

Black history in Taylor is rooted in the legacy of a groundbreaking physician who literally helped preserve the town’s well-being.

In the 1920s, James Lee Dickey settled with his wife in Taylor as the city’s only Black doctor.

He worked hard to address the public health needs of Taylor, calling for improvements to the water supply and helming a community effort to treat a typhoid-fever outbreak in 1932-33.

His clinic expanded to serve the surrounding area. He developed programs for infant care and was instrumental in admitting Black patients to state tuberculosis clinics.

Outside of the doctor’s office, Dickey led efforts to create local recreational facilities and federal housing, as well as helped to pass school bonds and improvements. He received numerous awards and honors, including distinction by the Taylor Chamber of Commerce as Man of the Year in 1952.

Bill Pickett

400 N. Main St., Taylor

Rodeo enthusiasts come to Taylor yearly for shows and competitions, and William M. “Bill” Pickett helped make the city a destination on the circuit.

Growing up in Taylor, Pickett worked as a cowboy in Central Texas and pioneered the art of “bulldogging,” which is when a cowboy jumps from his horse to twist a steer’s horns and force the bovine to the ground.

Decades ago, Pickett was one of the few Black cowboys on the rodeo circuit. He went on to perform in the United States, Mexico, Canada and Europe. In 1971, he posthumously became the first Black cowboy inducted into the National Cowboy Hall of Fame.

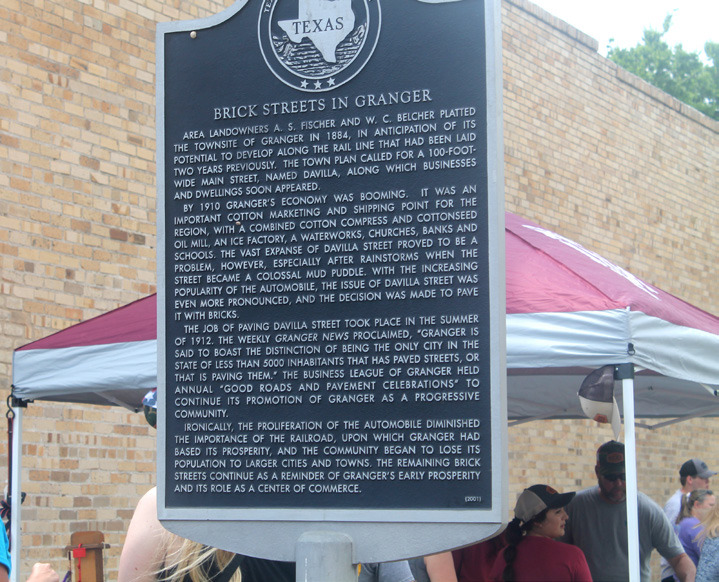

Brick Streets in Granger 203 W. Davilla St., Granger

Downtown Granger, the finish line of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and the land of Oz have one thing in common — a brick road.

In 1884, area landowners A.S. Fischer and W.C. Belcher platted Granger. The town plan called for a 100-foot-wide main street, named Davilla, along which businesses and dwellings soon appeared.

Rainstorms turned the roadway into a colossal mud puddle. As variations of a new invention called the automobile gained popularity, city leaders needed to decide what to do with Davilla.

Bricks were the answer and Davilla was paved in the summer of 1912.

“Granger is said to boast the distinction of being the only city in the state of less than 5,000 inhabitants that has paved streets, or that is paving them,” read an article in the Granger News of the era.

The Business League of Granger held annual “good roads and pavement celebrations” to continue its promotion of Granger as a progressive community.

Today, the city’s remaining brick streets are a reminder of Granger’s early prosperity and its role as a center of commerce.

Moravia School 1145 CR 389, Granger

Czech heritage is celebrated in east Williamson County, beginning with settlements in the mid-1800s.

Many 21st century residents are descendants of pioneers from Moravia, a historical region in today’s Czech Republic.

Moravian immigrants were attracted by Central Texas’ fertile soils and the hope for a better life. One of the early settlers was Pavel Machu, a native of the Vsetín Valley of the Czech Republic.

In 1884, Machu donated three acres of his farm for a community school named for his homeland.

S.E. Montgomery paid for the lumber and built the one-room schoolhouse, which also provided meeting space for church services and community activities.

Moravia School opened in 1884, replacing the earlier Dykes School. Charles Lord served as the first headmaster.

Moravia became Common School District No. 83 in 1903. It continued to serve the dispersed farming settlement and was a focal point for social and religious gatherings.

In 1922, trustees enlarged the schoolhouse to two rooms, providing space for grades one through eight. Older students attended high school in Granger.

By the 1930s, the declining agricultural population resulted in the closing of several area schools, and Moravia shuttered in 1945.

The district formally merged with the Granger Independent School District in 1949, and the Moravia schoolhouse was soon moved to Granger to the site of Crispus Attucks High School. There it remained until 1964, when the traditionally African-American school integrated with other Granger schools.

C.S.A. Cotton Cards Factory 771 Texas 95, Circleville

The Circleville community on Texas 95 between Taylor and Granger once housed a factory that played a critical role in the Civil War.

The C.S.A. Cotton Cards Factory from1862-65 used the nearby San Gabriel River to power the manufacture of war-era brushes for the Confederate States of America.

During the rebellion, retooling from an agricultural trade to a wartime footing made the production of cotton bales for finished cloth no longer practical in Texas.

Because textiles now had to be made at home, Texas imported through neutral Mexico, at costs of $4 to $20 a pair, thousands of cotton cards – stiff brushes that made fluffy cotton into firm, smooth “batts” to be spun into yarn or thread, quilted or made into mattresses.

After Gov. F. R. Lubbock took office in 1861, he led a charge to have the cards made at Texas factories, including the one in Circleville.

The facility was owned by Joseph Eubank Jr.

Heavy military demands and reduced imports prompted a rapid expansion of the industry.

Arms and munitions plants were built, and land grants were used to encourage production. Private efforts were said to meet the need and produced vital supplies for military and civilian populations, according to historians.

Comment

Comments