Local attorney turned governor lauded for getting justice in 1920s attack

ne hundred years ago this month, a district attorney from Taylor, an Austin judge and a Georgetown jury stood their ground in the face of death threats and managed to “break the spine” of the Ku Klux Klan in Texas, according to historians.

The attorney was Dan Moody, who would go on to serve two terms as Texas governor. His victory over the whitesupremacist organization, with the aid of others, is being celebrated in September during various local observances.

“During the 1920s and early 1930s, bad groups were gaining momentum in Europe. Had it not been for brave people like Dan Moody, the Ku Klux Klan might have accomplished similar results in the United States,” said Joe Burgess, chairman of Friends of the Moody Museum.

The museum is at 119 W. Ninth St. in Taylor.

“In 1999, Texas Monthly chose Dan Moody as the Crusader of the Century because he not only put his job on the line, but also his life in order to prosecute and send to prison members of the Klan,” Burgess added.

Moody secured guilty verdicts against Klansmen accused of abducting, assaulting and leaving for dead a traveling salesman named Ralph Waldo Burleson. Burleson was targeted because he boarded at the home of Fannie Campbell, a widow.

Though the Klan is infamous for attacks on people of color, Burleson and Campbell were Anglo.

“The Klan thought they were the keeper of our morals at the time, and they decided his relationship with this widow woman who was trying to care for her five children wasn’t appropriate, so they told him he should leave town. He didn’t because he wasn’t doing anything wrong,” Burgess said. “Burleson had been long-time friends with the widow and her deceased husband. There’s no indication the relationship was anything else.”

According to multiple sources, on Easter Sunday — April 1, 1923 — Burleson and Campbell, along with Campbell’s brother- and sister-in-law Lee and Carrie Jones, were driving from Jonah back toward Weir when they were surrounded by three carloads of men and forced to stop.

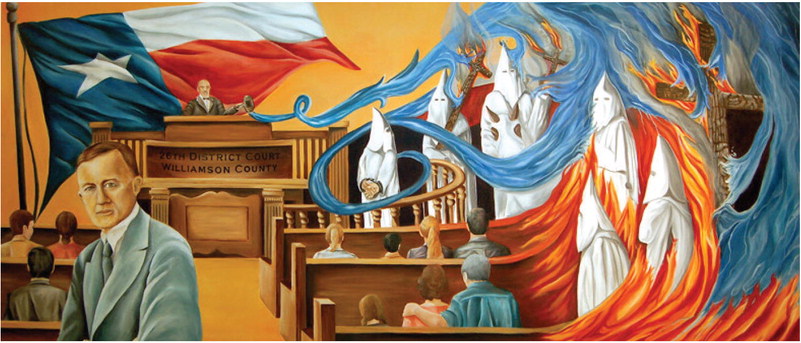

A mural depicting then-District Attorney Dan Moody of Taylor putting the Ku Klux Klan on trial a century ago this month hangs at The Williamson Museum in Georgetown. COURTESY THE WILLIAMSON MUSEUM

Four armed men ordered Burleson out of his car, began pistol-whipping him, then put a canvas sack over his head and loaded him into one of their cars where the witnesses could see they continued beating the victim, according to records.

None of the attackers were wearing hoods or masks, but their statements to the victim made it clear they were committing the act on behalf of the KKK, the witnesses testified.

The KKK was an insurgency movement spawned in the South after the defeat of Confederate forces in the 1860s by U.S. troops. Some cells still exist today.

Burleson was driven into Taylor, to an area on Lover’s Lane (now Lake Drive) about a half-mile west of what is now Main Street. There, a heavy chain was locked around his neck and used to pull him up against a thorn tree, where he was whipped with a leather strap at gunpoint until, according to a doctor’s testimony, he had almost no skin left from shoulder to knee and looked like raw steak.

The attackers then drove Burleson to the front steps of Taylor City Hall and tied him to a hackberry tree using the heavy chain. They removed the sack from his head, poured a bucket of creosote over him and left.

“They wanted him to die. They wanted him to be a warning to others. Their biggest mistake was how brazen they were. They weren’t worried about being caught,” Burgess said.

Burleson survived and was able to identify the four assailants who pistolwhipped him before he was masked.

At the time of the beating, Moody was the district attorney serving Williamson and Travis counties. A graduate of Taylor High School, he grew up with the men Burleson, Campbell and Carrie Jones identified.

Court records named the attackers as Murray Jackson, Olin Gossett, Dewey Ball and Godfrey Wayne Loftus, all of Taylor.

“In the 1920s, the KKK was very powerful in America and in Texas. They claimed over a million members and controlled quite a bit. They had their hands in a lot of political elections and you had a lot of corruption and basic racism all over,” said Dan Doss, a lifetime Taylor resident and member of the Williamson County Historical Commission. “There was a lot of intimidation from the Klan. Law enforcement was scared of them, people were scared of them.”

Doss said state District Judge James Hamilton, like Moody, was also eager to break the Klan’s hold on Texas. When the Burleson beating ended up on Hamilton’s docket, it proved to be just the right case.

“Dan Moody wasn’t going to be intimidated by the Klan, so he took them to court. The judge was Hamilton, who was pretty aligned with Moody. The various trials go from September 1923 to February 1924, but the first conviction was Sept. 25, 1923,” Doss said. “That was the first time (locally) a KKK member had been found guilty. It was Jackson, and he was sentenced to five years in prison.”

Although Moody would go on to convict a total of five men, from the beginning it was obvious he was really trying the KKK itself, according to Burgess. The Klan paid for the defense attorneys opposing Moody, and Moody questioned every defendant and defense witness about their Klan membership and activities.

“The Klan could have taken over. They controlled legislatures in not only Texas but states like Colorado and Oregon,” Burgess said. “The Klan had all this power and they were seeking more power. They wanted to get the top jobs in the state. But when this incident happened it was a real turning point. Everybody was watching, not only in Texas but also across the United States.”

The national attention helped propel Moody to election as attorney general of Texas, serving from 1925-1927. He then became the state’s youngest governor at the age of 33, serving two terms, 19271931.

“Being new to the area, I was just riveted immediately by the story. It is just so powerful. And it was local, it was right here in this still-existing historic (Williamson County) courtroom that this monumental event occurred,” said Nancy Hill, executive director of The Williamson Museum, 716 S. Austin Ave. in Georgetown.

“It’s one of the most popular and important things people want to know about when they do courthouse tours or museum tours,” she added. “People are fascinated by it. Riveted by it. When so much of our attention is consumed by controversial things, I think it’s wonderful to be able to point to the noble things that happened.”

Many hearing the story wonder how a hate-based organization could get such a foothold and have so much popular support. They are also surprised to hear that Burleson and Campbell were white.

“When we think of the Ku Klux Klan we obviously think of the things that happened with the Black community, but the hate was widespread: the Catholics, the Jews, anybody who wasn’t born here in the United States,” Burgess said. “And part of that really resonates because people were coming from Europe and taking over jobs. Part of the way the Klan got a foothold was they took a stand against all this immigration.”

The Klan also won popular appeal because it helped unwed mothers, took stands against alcohol, gambling and wife abuse, and acted as a social and business networking club, according to historians.

“Groups that have the same sorts of aims and tactics almost as the KKK still exist,” Hill said. “It is incredibly relevant for people to remember history so they can recognize behavior that’s going on all around us.”

“It relates a lot today with all the racial strife and other controversy that goes on. We hear Black people say they’re not welcome at events at the courthouse because the statue of the Confederate monument on the square makes them feel unwelcome,” Doss said.

Groups that venerate a connection to the defeated Confederate States of America also make some residents feel uncomfortable, especially if members wear Confederate gray uniforms, Doss added. However, representatives of such organizations say their purpose is to remember history, not promote racial divide.

Burgess said Moody’s win against the KKK had wide-ranging effects, and district attorneys from other states copied his strategy successfully.

“We all have an opportunity to do what’s right. It’s a choice. People in our past have made good choices and we need to to do the same today because we’re facing a lot of the same issues,” he said.

The Moody Museum and The Williamson Museum are celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Moody’s victory over the Klan with a series of events.

DAN MOODY CELEBRATIONS

7 P.M. • SEPT. 6

Williamson County Courthouse, 710 Main St., Georgetown Viewing of “Klan on Trial,” the Dan Moody documentary produced by Chet Garner, sponsored by the Williamson Museum, the Moody Museum and the Williamson County Historical Commission. Free admission, but tickets are required due to limited capacity. Reserve tickets at williamsonmuseum.org.

SEPT. 29 - OCT. 15 7 P.M. FRIDAYS & SATURDAYS 2 P.M. SUNDAYS

A Georgetown Palace Theatre production, “You Can’t Do That Dan Moody,” will be performed in the historic Williamson County Courthouse, 710 S. Main St., Georgetown.

TICKETS ON SALE AT THE THEATER BOX OFFICE, 810 S. AUSTIN AVE., AND THROUGH WWW.GEORGETOWNPALACE.COM.

Comment

Comments